A Review of the Autonomic Nervous System and Why It’s Important

Picture credit: https://nataliarachel.medium.com/the-autonomic-nervous-system-explained-34a0ddd24553

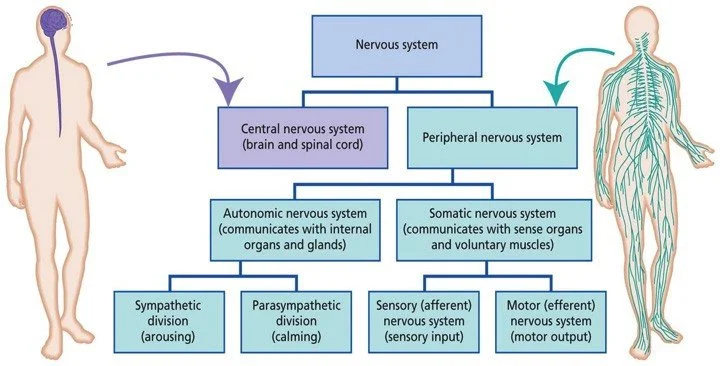

Here is a basic breakdown of how our Nervous System can be divided based on anatomy and function. This blog post focuses on the Autonomic Nervous System - maybe I will review the other divisions in another one :)

Throughout our day we receive a steady stream of external inputs from the environment that is detected by our sensory organs (eg. eyes, ears, skin, nose, etc). Multiple areas in the brain then integrate and process these sensory inputs with other factors, such as one’s level of alertness and concentration, and memories of similar events, to produce a decision about whether there is actual or perceived potential for physical injury or death. Additionally, actual or perceived threats to our personal ‘ego’ (ie. how we view ourselves), such as rejection, negative evaluation, fear of or exposure to failure, or shame can produce similar physiological responses to those of physical stressors/threats (1).

If the brain concludes that a danger, threat, or stressor has occurred it will trigger a cascade of Physiological responses (ie. chemical, hormonal, electrical, etc), controlled by out Autonomic Nervous System, to help our body respond appropriately.

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM: BRIEF OVERVIEW

The Autonomic Nervous System is involved in the unconscious regulation of bodily functions, such as the resting tone/tension in our skeletal muscles and movements of the heart, digestive and urinary systems, pupils, and lung airways.

It can be divided into opposing systems:

Sympathetic Nervous System: “Fight, flight, or fright”

Parasympathetic Nervous System: “Rest or digest”

The Sympathetic Nervous System is involved with responding to threat, stress, and danger. It’s intention is to produce fast-acting, short-term responses so that we can appropriately protect ourselves from what the body perceives as imminently harmful/threatening. Some examples of these “survival mode” stress/danger responses include priming your body for action by tensing muscles involved in mobilizing the body, dilating pupils, increasing heart rate and breathing rate, and opening our airways. These would all be helpful if you were to hear the grunts of a big animal while hiking in the woods.

The Parasympathetic Nervous System contrasts the Sympathetic system by promoting digestion, excretion of wastes, immune system activity, and a relaxed state. These are all functions that are not necessary for your immediate safety during a dangerous or threatening experience. In these situations the activity in the Sympathetic system will become more dominant and the Parasympathetic system will become inhibited.

Normally, we have an effective balance between Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Nervous System activity/arousal, which allows our body to respond to stress-producing events, appropriately, and return to a more restful state afterwards.

Our body is capable of experiencing, processing, and recovering from life’s stressors and ‘mild’ traumas. In fact, the accumulation of these experiences, and our body’s recovery from them, helps shape every aspect of who we are and how we interact with the world, including our physical and mental health (2).

However, if we experience a significant traumatic event or if we are under chronic and/or repeated stress the scale may tip towards greater, and more prolonged, Sympathetic activation (3). If this takes place for a sustained period or occurs repeatedly it can cause the Sympathetic responses to go into overdrive and potentially lead to adverse outcomes (1,3), such as prolonged tension of muscles involved in the fight-flight response, elevated blood pressure, or issues relating to your digestive and immune systems. See my blog post on Insights into Stress and Trauma for more info about this.

Modern day living often involves frequent (or near constant) triggering of the stress response, even though we may not be in mortal danger. Examples may include work/school deadlines, public speaking, being late for an appointment or in paying bills, health consciousness amidst a global pandemic, or others. Our body’s responses to these non-life-threatening stressors are remarkably similar to the life-threatening ones because they both can lead to increased Sympathetic Nervous System activation (1).

For the reasons outlined above, the importance of recognizing and acknowledging the presence of stress/trauma, taking action and seeking help, and maintaining your efforts should not be understated. Working with a qualified health professional (multiple healthcare professions are capable of helping with this) and using self-help techniques, such as grounding and mindfulness, can help bring your body back into a more balanced state of Being.

REFERENCES

(1) Ronhovde, S. (2021). Module 1 and 2 lectures [powerpoint notes]. Retrieved from Global TRE® Certification Training.

(2) Scaer, R. C. (2005). The trauma spectrum: Hidden wounds and human resiliency. WW Norton & Company.

(3) Sapolsky, R.M. Stress and Plasticity in the Limbic System. Neurochem Res 28, 1735–1742 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026021307833

- Thanks for reading and keep looking for more posts in the future on other ‘hot topics’ in the world of Physiotherapy and Physical Rehabilitation!